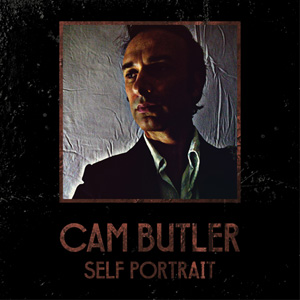

Cam Butler - Self PortraitIf you wanted, or needed, to travel a vast distance - perhaps between continents, or further, between planets - then Cam Butler's new album Self Portrait would not only be your soundtrack, but your companion. It's a textured roadmap, rich and densely coloured, a hand-painted manuscript to set a course by in the evenings of solitude and the days of searching.

Self Portrait builds on Cam's earlier work, from Silver Ray to The Shadows of Love, riding deep into a guitar-based world of soaring emotional landscapes. Peaks of shimmering sound emerge from layered drifts of electronic looped backings, as if the guitar was floating on a cushion of chords. His unique style carries you effortlessly through the clouds, surrounded and encased by soulful and aching symphonies. From the opening sway of Something's Wrong to the listless writhing of the late Roland S Howard's The Golden Age of Bloodshed and on through the haunting chambers of Space, Cam's guitar is a voice of its own, calling and guiding, lilting and sharp by equal measures. He finishes with an astonishingly savvy rendition of Duke Ellington's In A Sentimental Mood, capturing the contrapuntal shifts that give the song its aching sense of longing. If you need a soundtrack for a flight from the everyday, or for an interstellar expedition beyond Jupiter, Self Portrait will be a compelling co-pilot. Published April, 2014 http://www.cambutler.com/ |

Glass Psyche - catalogue essay

In Gerald Durrell's acclaimed short story The Entrance, the protagonist is both haunted and hunted by an apparition that moves without reason or logic, carving itself out of the mirror of recognition. Without recourse to the security of accepted notions of reflection and seeing, the world is called into mutable unease, where accepted and expected desires are shattered

Heidi Yardley's newest work, Glass Psyche, inhabits this world of benign malevolence, interrupting sylvan glades with carved, unexpected intrusions of displaced beauty that mar the safety of a remembered landscape; that contrast a notion of peacefulness with an unsettling eroticism.

As in the realms of dream, images hover in the foreground, pulling the viewer toward a luminous beauty that belies the sharp edges of both the craft that has seduced them and the comprehension they seek, to deliver a supernatural discord that recalls the gothic displacement of Ann Radcliffe, Clara Reeve and Angela Carter: the feminine blade of apperception applied to the ideal of colonial possession; the night's sweet whisper of comfort made disquiet.

Published October, 2013

http://heidiyardley.com/home

Heidi Yardley's newest work, Glass Psyche, inhabits this world of benign malevolence, interrupting sylvan glades with carved, unexpected intrusions of displaced beauty that mar the safety of a remembered landscape; that contrast a notion of peacefulness with an unsettling eroticism.

As in the realms of dream, images hover in the foreground, pulling the viewer toward a luminous beauty that belies the sharp edges of both the craft that has seduced them and the comprehension they seek, to deliver a supernatural discord that recalls the gothic displacement of Ann Radcliffe, Clara Reeve and Angela Carter: the feminine blade of apperception applied to the ideal of colonial possession; the night's sweet whisper of comfort made disquiet.

Published October, 2013

http://heidiyardley.com/home

Nature's Folly - catalogue essay

The work in this exhibition deliberately ranges from sharp and structured images to partially-cleared soft-focus landscapes,

travelling and exploring the contrast between the architecture of the ‘tamed’ land and ‘the garden’, and the wilderness that is

ravaged, eroded or drought-stricken.

In this there is a suggested battle between nature and man, and yet a complicity - that as much as we consider ‘Nature’ as a foreign entity and a thing to be controlled and conquered, we are, in every instant, part of that nature and directed by it. The more effort

we use to make a ‘natural’ world, the greater our sense of isolation and distance when we are confronted with the true wilderness, and our colonial sense of righting the ‘unnatural’ disorder is affronted. We fence, align, straighten and cut. We mow, divide and place ourselves at the centre. We impose our ancestry like a child’s blanket, securing our tenuous and easily-broken grip on a

fragile and ancient land, closeting our fear of a foreign nature that seems to seek retribution.

What is ‘the garden’? Why do we desire it so much? How can we hope to shape a garden in a dry, damaged environment?

Gardens, parks, vistas - they seduce us with their theft of views, their artful rearranging of perspectives, their denials of an

expected space. They trick us with follies and grottos that speak with a seeming ancient tongue, that promise dark spaces

whispering of long-disappeared worlds. Castles of chicken wire and concrete, plaster and paint, populated with statues of

maidens and heroes, promising an exciting journey.

These monuments, fountains, porticos and grottos remind of us our mortality as much as marble gods are immortal. Keats tells

us of the sweet heard and sweeter unheard melodies - these imagined worlds fill our minds with their silent melodies, allowing

us to, however briefly, escape the clutches of time. Reverie overtakes us in the garden; we are swallowed by our own thoughts. Histories, real and fabricated, have their home here.

Some of these works focus on silhouettes, skylines, outskirts, fringes, remembered spaces and forgotten dwellings. The fountain represents the harness of nature, a combination of engineering and an artistic expression of beauty, with particular reference to

the perversity of a fountain in a place where there are floods and droughts beyond our control.

The stitched panoramas were inspired by the 360-degree views from our home. In the panoramas the monuments and grounds are recomposed into an imagined world like a still life. We are constantly struggling with our desire to tame, shape, adorn and inhabit our patch. An interest in old maps and garden plans arises from this. Here there is also a reaction to detritus, longing for beauty in

a place where the traditional response has often been to clear, to grade and to build over the unwieldy and fence the desirable.

Published June, 2013

http://www.tiffanytitshall.com/

travelling and exploring the contrast between the architecture of the ‘tamed’ land and ‘the garden’, and the wilderness that is

ravaged, eroded or drought-stricken.

In this there is a suggested battle between nature and man, and yet a complicity - that as much as we consider ‘Nature’ as a foreign entity and a thing to be controlled and conquered, we are, in every instant, part of that nature and directed by it. The more effort

we use to make a ‘natural’ world, the greater our sense of isolation and distance when we are confronted with the true wilderness, and our colonial sense of righting the ‘unnatural’ disorder is affronted. We fence, align, straighten and cut. We mow, divide and place ourselves at the centre. We impose our ancestry like a child’s blanket, securing our tenuous and easily-broken grip on a

fragile and ancient land, closeting our fear of a foreign nature that seems to seek retribution.

What is ‘the garden’? Why do we desire it so much? How can we hope to shape a garden in a dry, damaged environment?

Gardens, parks, vistas - they seduce us with their theft of views, their artful rearranging of perspectives, their denials of an

expected space. They trick us with follies and grottos that speak with a seeming ancient tongue, that promise dark spaces

whispering of long-disappeared worlds. Castles of chicken wire and concrete, plaster and paint, populated with statues of

maidens and heroes, promising an exciting journey.

These monuments, fountains, porticos and grottos remind of us our mortality as much as marble gods are immortal. Keats tells

us of the sweet heard and sweeter unheard melodies - these imagined worlds fill our minds with their silent melodies, allowing

us to, however briefly, escape the clutches of time. Reverie overtakes us in the garden; we are swallowed by our own thoughts. Histories, real and fabricated, have their home here.

Some of these works focus on silhouettes, skylines, outskirts, fringes, remembered spaces and forgotten dwellings. The fountain represents the harness of nature, a combination of engineering and an artistic expression of beauty, with particular reference to

the perversity of a fountain in a place where there are floods and droughts beyond our control.

The stitched panoramas were inspired by the 360-degree views from our home. In the panoramas the monuments and grounds are recomposed into an imagined world like a still life. We are constantly struggling with our desire to tame, shape, adorn and inhabit our patch. An interest in old maps and garden plans arises from this. Here there is also a reaction to detritus, longing for beauty in

a place where the traditional response has often been to clear, to grade and to build over the unwieldy and fence the desirable.

Published June, 2013

http://www.tiffanytitshall.com/

Natural Recycling - from flooring to framing

The picture frames you see in Tiffany Titshall’s exhibition Nature’s Folly are all made from recycled timber - the flooring of the old kitchen skillion of her home, the former schoolmaster’s residence in Majorca. In 2009, over a bottle of Amherst wine at the property, building designer Peter Rechenberg talked with Tiffany and her husband about the proposed demolition of the dilapidated 1930s extension to the 1890s residence, and instantly drew a quick sketch of what he thought the replacement building should be. The owners agreed, and began discussing with Peter the importance of recycling, of designing and constructing a building suitable to the harsh environment of the area, and of making that building passive-solar, modern and not overwhelming upon both the narrow footprint of the former school site and the old house.

Over time, a number of weekends spent in the old house, collaborating on ideas and materials, including recycled bricks sourced from the old Alexander Miller Memorial Homes in Maryborough, a final design was produced. At around the same time Central Goldfields Shire Council Arts Manager Kay Parkin offered Tiffany a solo exhibition, the rear of the house was demolished by hand in order to conserve as many recyclables as possible. The flooring of the kitchen, which had been replaced at some point between 1950 and 1970, was painstakingly taken up, de-nailed and sorted. Over the twelve years the couple have lived in Majorca, and long before, those boards had been used as a dance floor, had seen snakes and lizards crawling over them, and a couple of generations of echidnas living under them.

The boards were Eucalyptus regnans, commonly known as mountain ash or Tasmanian oak. Tiffany and her husband Caleb Cluff broke the boards down to length and width, thicknessed them and routed rebates, sanded and oiled the stock, and delivered them to Ralph Durr in Talbot to be guillotine-mitred. Tiffany realised the timber’s native colour and years of marking and scarring matched the slightly washed-out hue of the pale inks and starkly contrasting charcoals of her works on paper. This integration of material and idea has contributed to the richness of an exhibition drawn from the experience of living within a landscape still damaged, and still in recovery from mining, clearing, fire and drought, and the extreme seasons of the Victorian goldfields; compared with travels through more structured landscapes and gardens.

Published May/June, 2013

http://www.tiffanytitshall.com/

Over time, a number of weekends spent in the old house, collaborating on ideas and materials, including recycled bricks sourced from the old Alexander Miller Memorial Homes in Maryborough, a final design was produced. At around the same time Central Goldfields Shire Council Arts Manager Kay Parkin offered Tiffany a solo exhibition, the rear of the house was demolished by hand in order to conserve as many recyclables as possible. The flooring of the kitchen, which had been replaced at some point between 1950 and 1970, was painstakingly taken up, de-nailed and sorted. Over the twelve years the couple have lived in Majorca, and long before, those boards had been used as a dance floor, had seen snakes and lizards crawling over them, and a couple of generations of echidnas living under them.

The boards were Eucalyptus regnans, commonly known as mountain ash or Tasmanian oak. Tiffany and her husband Caleb Cluff broke the boards down to length and width, thicknessed them and routed rebates, sanded and oiled the stock, and delivered them to Ralph Durr in Talbot to be guillotine-mitred. Tiffany realised the timber’s native colour and years of marking and scarring matched the slightly washed-out hue of the pale inks and starkly contrasting charcoals of her works on paper. This integration of material and idea has contributed to the richness of an exhibition drawn from the experience of living within a landscape still damaged, and still in recovery from mining, clearing, fire and drought, and the extreme seasons of the Victorian goldfields; compared with travels through more structured landscapes and gardens.

Published May/June, 2013

http://www.tiffanytitshall.com/

| naturalrecycling.pdf |